To work in science, train students and not have to zig-zag from the Communist Party

Stáhnout obrázek

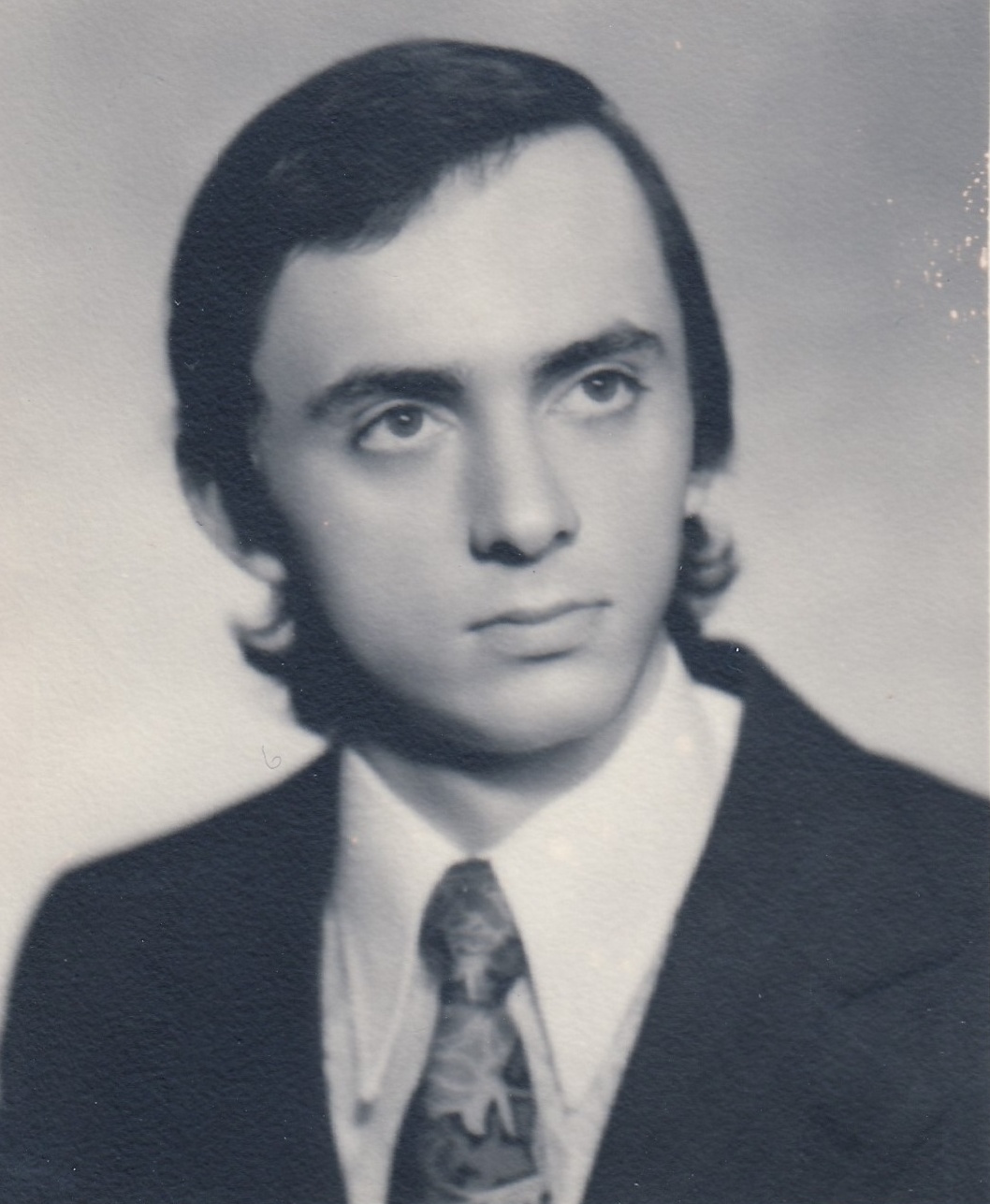

Libor Grubhoffer was born on April 30, 1957 in Polička. He grew up in the village of Oldřiš u Poličky where his parents ran an inn called Na Bělidle. Between 1972 and 1976 he attended high school in Polička and was president of his school`s branch of the Czechoslovak Socialist Union of Youth. In 1981 he completed his Master`s Degree at the Faculty of Science of Charles University in Prague. He wanted to continue his studies there but was not cleared to do so by the university`s youth unionists. Mr. Grubhoffer did his compulsory military service in 1981 and 1982 with a tank battalion in Jihlava. After conscription he was employed in the Research Institute for Organic Synthesis in Pardubice which he left within the year to work under Assistant Professor Dimitrij Slonim, M.D. at the Prague Institute of Sera and Vaccines. In 1986 he transferred to the Parasitology Institute of the Biology Center of Czechoslovak Academy of Science in České Budějovice. He took an active part in the process of democratization of the Academy of Science during the Velvet Revolution in 1989. In 2001 Mr. Grubhoffer was made professor of molecular and cellular biology and genetics. He was dean of the Faculty of Biology of the University of South Bohemia between 2004 and 2011 and president of the University between 2012 and 2016. In 2019 he was living in České Budějovice and working as director of the Academy of Science Centre for Biology there.