We were quite scared, but the army was not to enter Budějice

Stáhnout obrázek

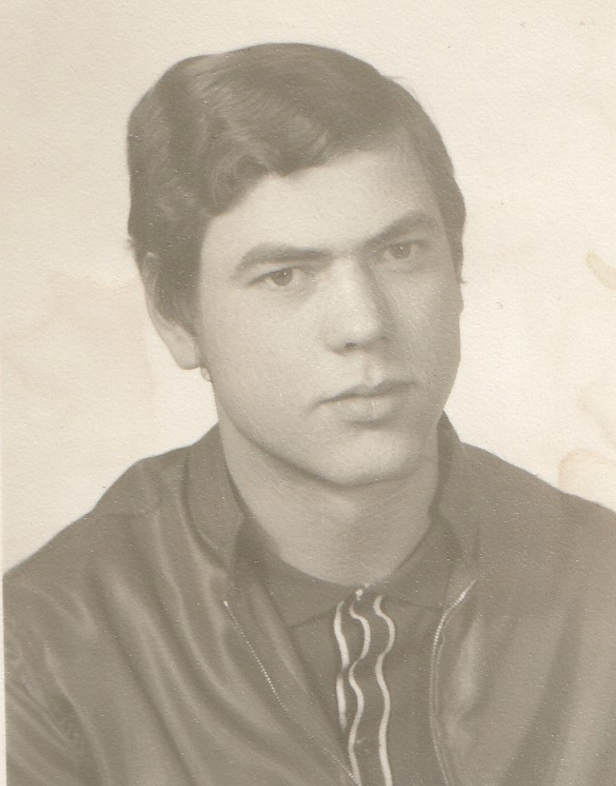

Petr Jauker was born on 22 February 1950 in a repatriation camp in České Budějovice. He comes from a Czech-German marriage. His father fought in the Wehrmacht, from which he deserted, and was therefore in a prisoner of war camp; his mother‘s side of the family was in the camp because its members had declared their German nationality during the war. After the war, however, the family was not deported because the father was engaged in a desirable trade, that of an automobile fitter. Petr Jauker trained as an auto mechanic in 1968 and changed several jobs, in addition to plumbing at ČSAO (Czechoslovak Automotive Repair Works), for example, delivering goods, driving or repairing a historic trolleybus. For the longest time, for twenty years, he worked at the České Budějovice heating plants as a heavy machinery engineer, where he later became a trade unionist and was instrumental in significantly increasing the wages of the employees. Petr Jauker has vivid memories especially of the days of the August occupation, when he was a direct participant in the erection of the barricade at Borek, which prolonged the entry of the troops into the town by one day, he was present at the tearing down of the star from the building of the Regional National Committee (KNV), as well as he was present, for example, at the České Budějovice radio station, which the crowd defended in order to preserve the broadcast. In 2023, Petr Jauker was living in České Budějovice.