“It was such a process and today I think about that human ethic, morality and justice. These are questions I’m unable to answer because it’s not possible at all.”

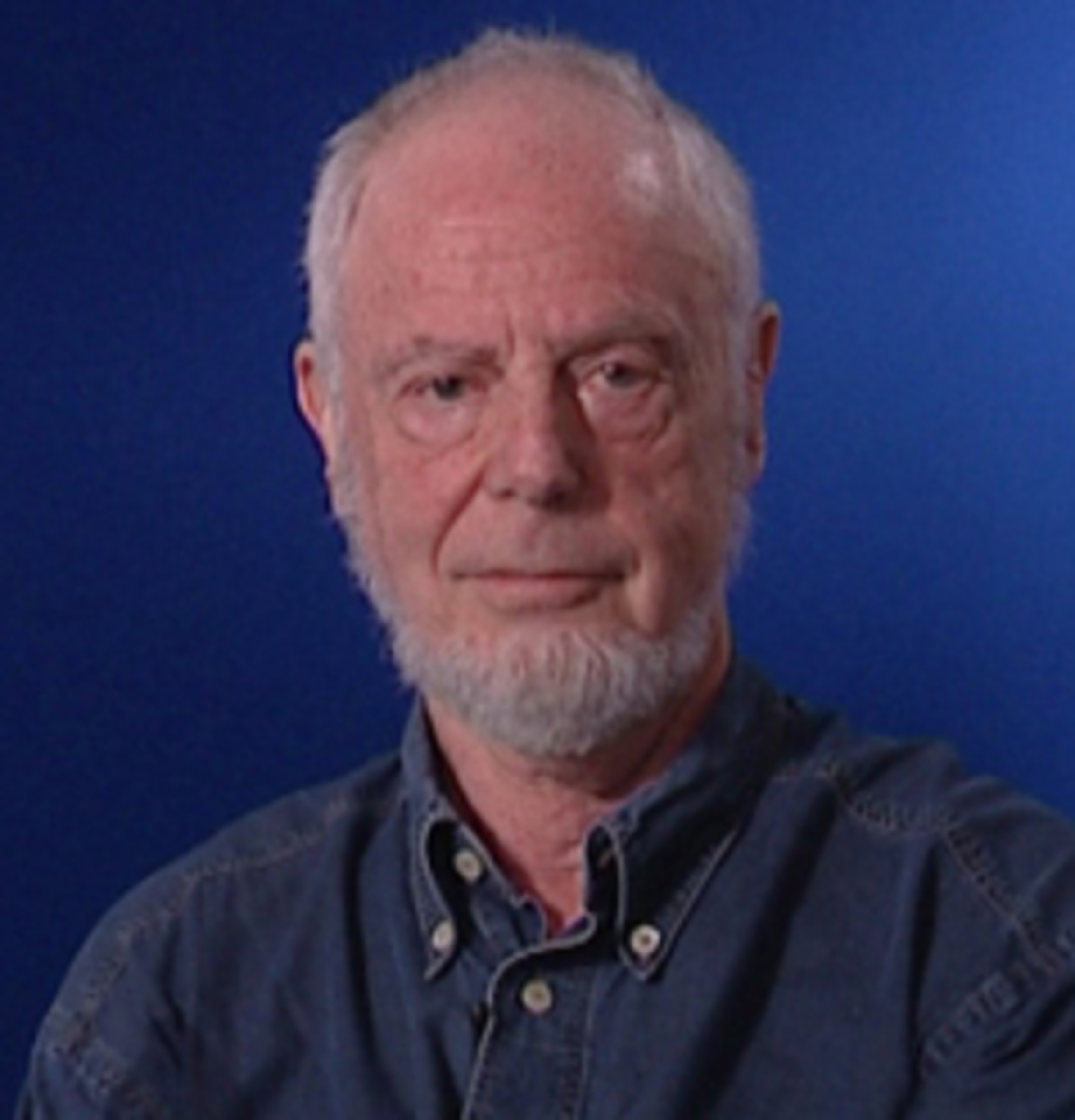

Ján Lenský was born on January 27, 1928 in Prague. He comes from a Jewish family, but his parents were never active as for their religion, they didn‘t abide by the traditions, they preferred the way of assimilation. Ján used to be shy as a child and he often felt lonely; moreover, tense pre-war atmosphere left scars on him, too. Later, he managed to gain his lost self-confidence thanks to the violin playing, which he has excelled in since his early childhood. He attended municipal school and later grammar school in Prague. Beginning of the Second World War meant the stop-out of his grammar school studies. Aryanization affected also his father. They deprived him of his shop. In 1939 the whole family got themselves christened, what initially saved them before being sent to concentration camps. In winter 1941, when the situation in Czech Republic sharpened, the whole family decided to flee to Slovakia, where the atmosphere was relatively calm at that time. They arrived in Levoča, where they lived for some time. After the outbreak of the Slovak National Uprising they were forced to flee from Germans, so they joined a partisan group as civilians. Ján‘s parents weren‘t able to walk in the mountains, so they returned back to the town. They were immediately deported to concentration camps. Ján kept going with partisans, but at last he gave it up as well. Then he managed to stay in hiding in Levoča and in the village of Kolačkov. After the end of war and many long years of separation, the family finally reunited in Prague. Ján pursued his grammar school studies and passed the school leaving exam. In 1947 he left for London, where he managed to get a scholarship at the prestigious Royal College of Music. In the year 1958 he started working as a violin player and conductor for an English opera ensemble, where he also met his second wife. They married in 1961. In this period of time he also met a lot of highly regarded musicians and conductors. He decided to immigrate to the USA along with his wife, an opera singer. They stayed in New York. Since 1970 they have lived and worked in Germany, where was Ján Lenský fully devoted to music.