In the labour camps, we scouts had immense street cred.

Stáhnout obrázek

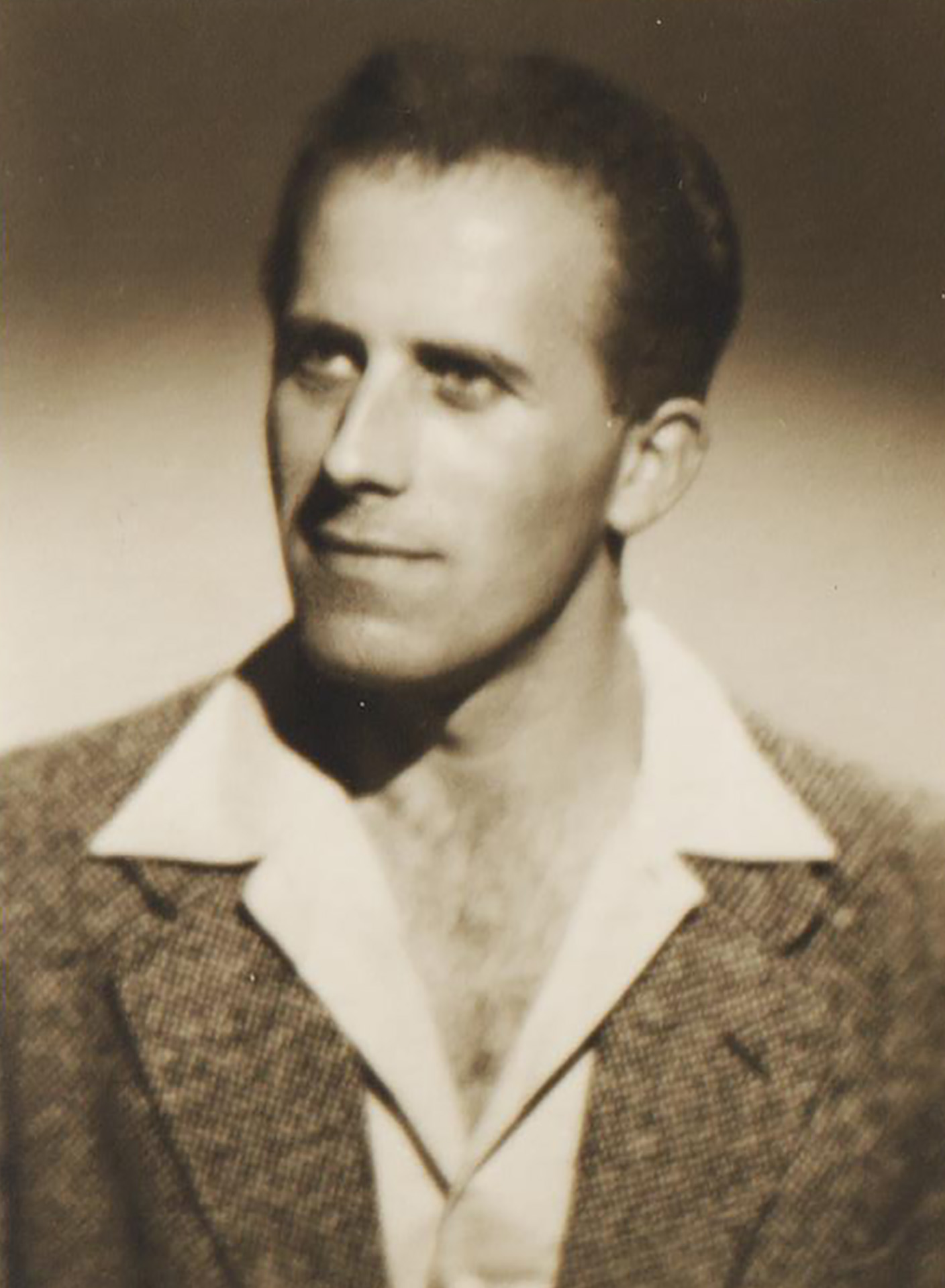

Jiří Lukšíček, nicknamed Rys [Lynx], was born on the 16th of August in 1933 in Prague. In 1945, he joined the Junák/Scout. He was the member of the 100th and later the 145th group. After the 1948 coup d’état when the Junák/scout movement was being gradually disbanded, Jiří jouned the scouts’ resistance group who mainly distributed anti-Communist flyers and later on, acts of sabotage. The group gradually armed themselves with seventeen handguns. In March 1953, after a failed sabotage in the vicinity of the Jílové village, he was arrested for the first time and together with two other scouts, they got their prison sentences. Jiří served two months in a labour camp Svornost [Unity] and after two months, he was released in an amnesty. After his release, he served in the army with the Auxiliary Technical Batallions in Hradec Králové. There, he was arrested again and tried again along with the Ostříž group members. Since the group was armed, they were accused of and tried for treason. This time, Jiří was sentenced to six years of imprisonment which he spent in the labour camps of Nikolaj and Rovnost [Equality]. In 1960, he was released and started to work in the ČKD factory, first as a line worker, later, he taught at the factory-run secondary technical school. In 1968, he reestablished the 233rd scout troop under the 34th scout centre, Ostříž [Falcon]. He tried to keep the troop going even after the scouts were banned again at the beginning of 1970. In the same year, he was forbidden to work with the youth. After the 1989 revolution, he became the head of the scout centre and an active member of Junák.

![Jiří Lukšíček - Rys [Lynx] (right) and Jiří Oktábec - Grizzly (left) preparing for the semi-legal scouts' summer camp. May 1967](https://www.memoryofnations.sk/sites/default/files/styles/witness_gallery/public/2020-11/1967-kv%C4%9Bten%2C%20p%C5%99%C3%ADprava%20na%20t%C3%A1bor%20Karolinka.jpg?itok=HNuaYjK9)

![New Year's Eve party in 1968 at the Lukšíček home. From left: Jindřich Valenta - Vlk [Wolf], Oldřich Rottenborn - Hoby, František Bobek - Stopař [Stalker], Jiří Lukšíček - Rys [Lynx], and Jiří Oktábec - Grizzly.](https://www.memoryofnations.sk/sites/default/files/styles/witness_gallery/public/2020-11/1968%20-Silvestr%20u%20Luk%C5%A1%C3%AD%C4%8Dk%C5%AF.jpg?itok=GH5SPCCw)