I thought to myself: “Gracious God, I won’t survive till the end of the shift.”

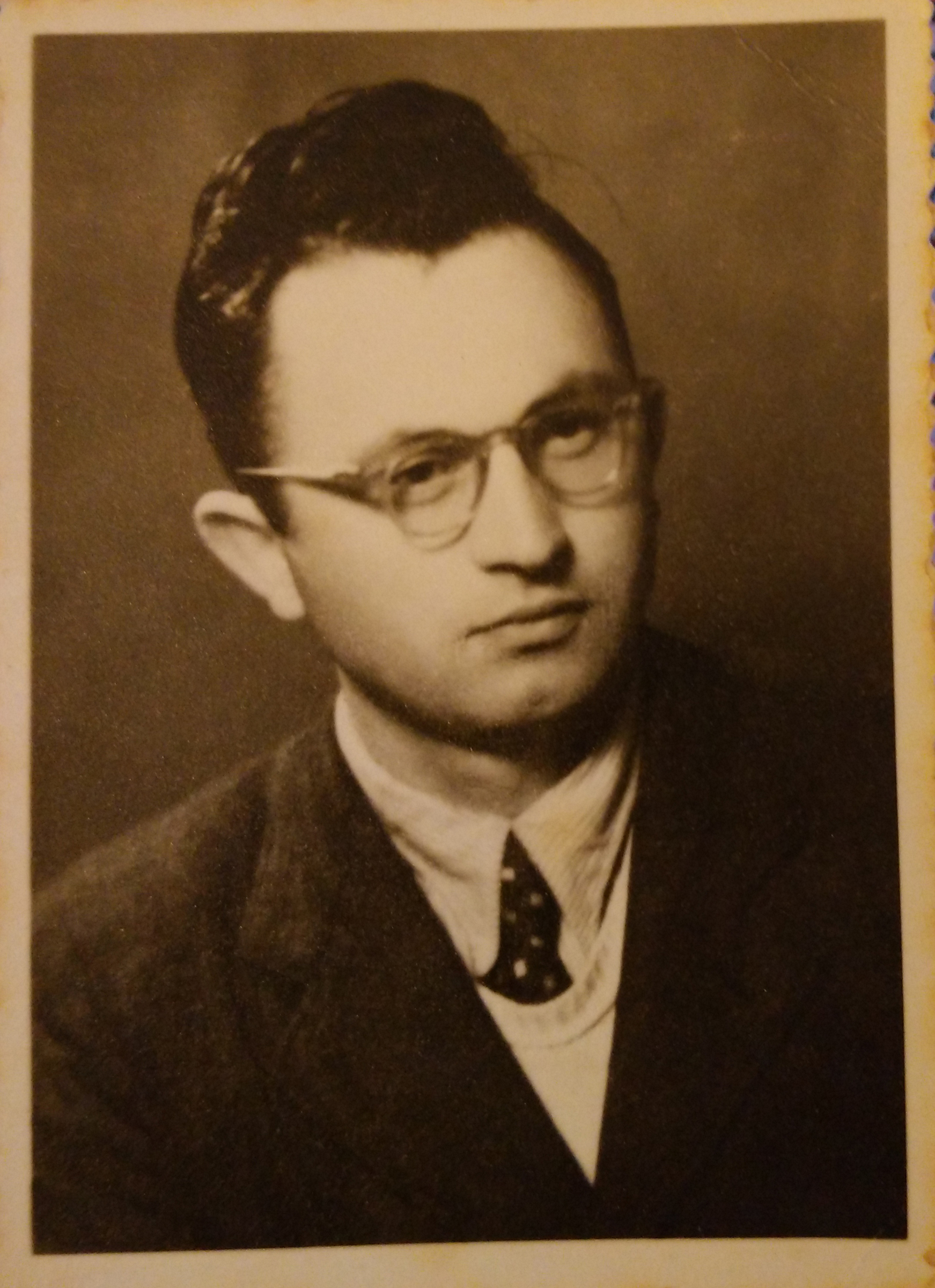

Vojtech Mikláš was born on October 20, 1928 in the village of Veľké Chyndice near Vráble. His parents Mária and Vincent were farmers. After 1938 his home village was annexed to Hungary and so Vojtech studied at grammar school in Budapest. He didn‘t finish his studies because of front-line combats. After the war he attended grammar school in Nitra and wanted to become a priest. In 1950 he was labeled as politically unreliable person and was taken to Auxiliary Technical Battalions, where he spent almost three years. He was released in December 1953 on parole that he would serve one more year in his local military quarters. Later he managed to complete evening school with school leaving examination, but during the whole communist regime he had to work only as a manual worker. Currently he lives in Jelšovce near Nitra.