I was still pushed away from the truth

Stáhnout obrázek

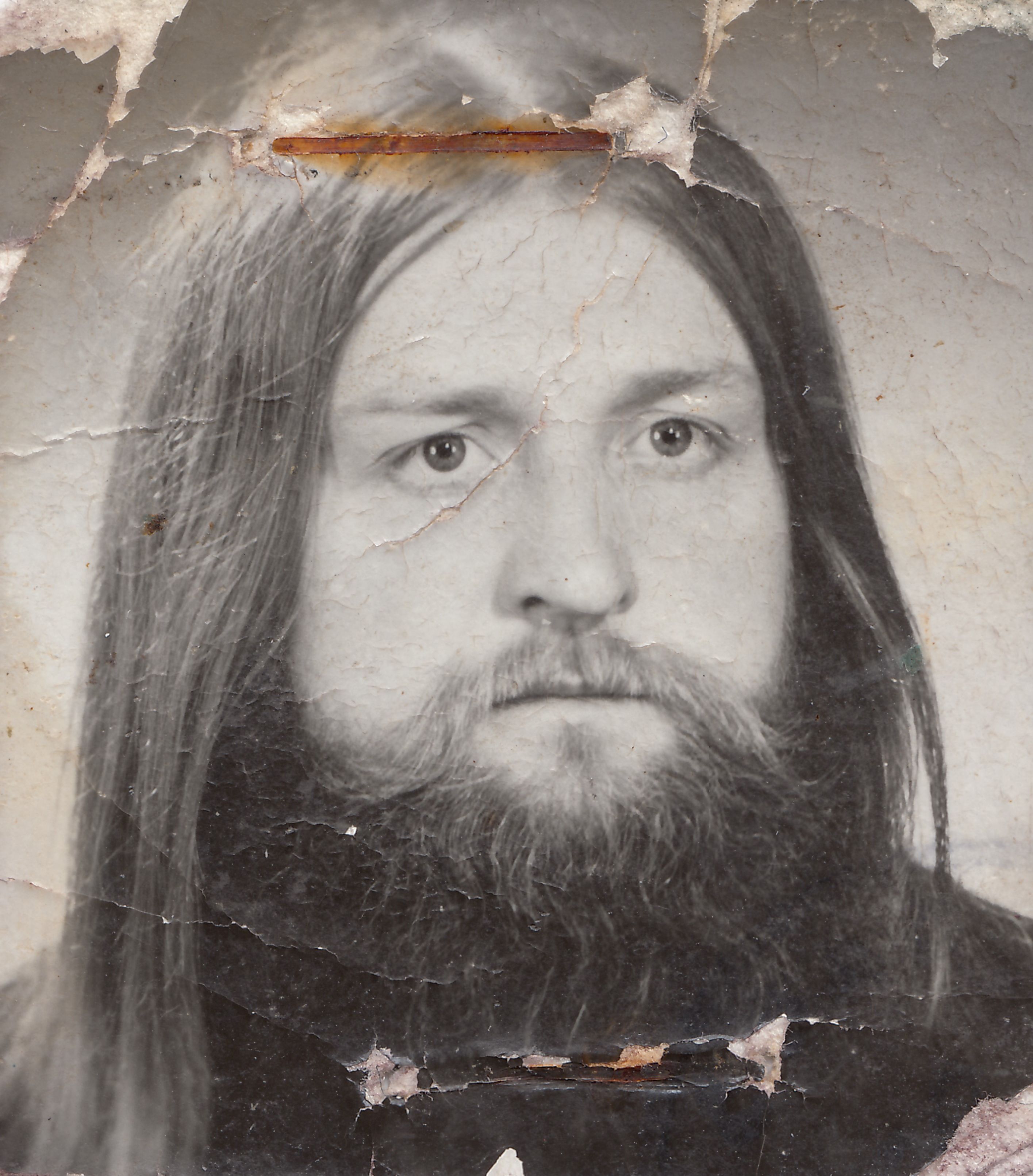

Lubomír Sapoušek was born on 11 June 1957 in Karlovy Vary. His father, Tomáš, served in the Border Guard, and he and his son often argued about politics. His mother, Marie, worked as a laundry worker. His worldview was shaped by the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops on 21 August 1968, which he experienced in Karlovy Vary and the Slovak village of Vysoká pri Morave. In 1973 he started an apprenticeship at the Karlovy Vary municipal construction company. He served his military service in Brno. He worked for communications as a maintenance worker and carpenter for ten years. He made friends with people from the underground and signed Charter 77 in 1986, after which State Security (StB) summoned him for interrogation. From 1988 onwards, he participated in several anti-communist demonstrations in Prague and, luckily, escaped arrest on 28 October 1988. He also went to demonstrations in Prague during the Velvet Revolution and took leaflets and published materials to Karlovy Vary. In 1990 he started working in his own joinery shop. He has two children from his first marriage. At the time of the interview (2021), he was living in Boží Dar with his second wife, Jaroslava Bartošová, with whom he raised his son Jan.