To tell the truth to everybody, no pretence.

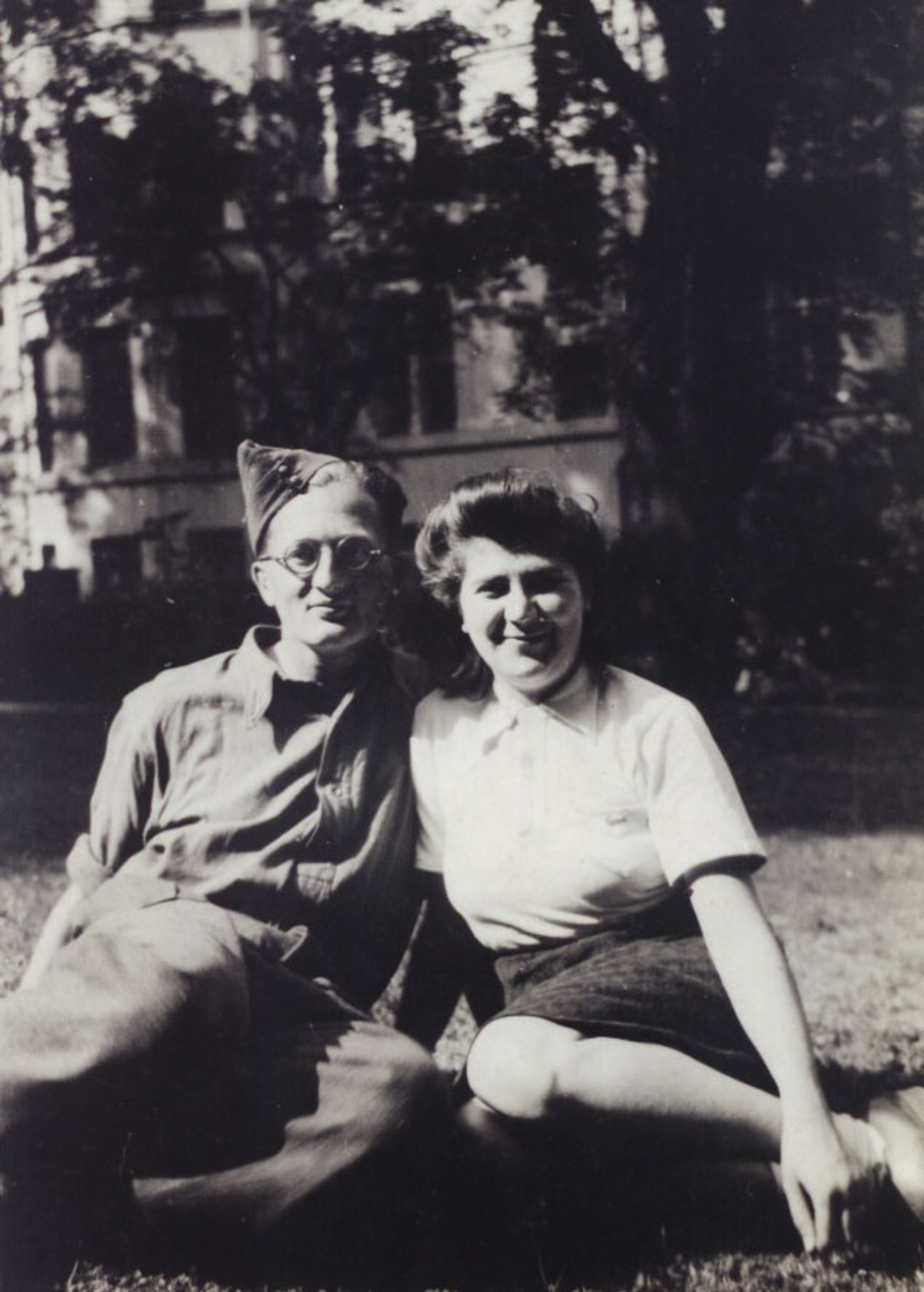

Bedřich Schalek was born on July 22, 1913 in a German family in Litoměřice. His father was a regional high judicial councillor. His mother died in 1918 of the Spanish flu. It was only from his father‘s second wife that Bedřich learnt Czech. He studied in a German elementary school and a grammar school. He did not finish his grammar school studies and he undertook training as a tanner instead. In 1935, he joined the communist Youth union. He held anti-Nazi views and after the Munich conference he had to leave Litoměřice. In January 1939, he was granted asylum in England. There he worked as a forest worker and in 1941, he married a Hungarian emigrant of Jewish origin. In 1942 their son was born. In November 1941, he joined the Czechoslovak army in England. He went through infantry training; he was assigned to the sappers. In August 1944, he was reassigned to Normandy and took part in fighting in the Belgian town of Bergues where he was wounded. In May 1945, he arrived with the Czechoslovak units to the already liberated Czechoslovakia. In August of the same year, he was demobilized and settled in Litoměřice with his family. In 1949, he was dismissed from his position as an interpreter at the Ministry of Interior, due to his participation in the English resistance. In 1950, through 1968, he was working as an editor in a German magazine. After voicing his disapproval with the Soviet occupation he was forced to retire.