To be doing something that‘s useful

Stáhnout obrázek

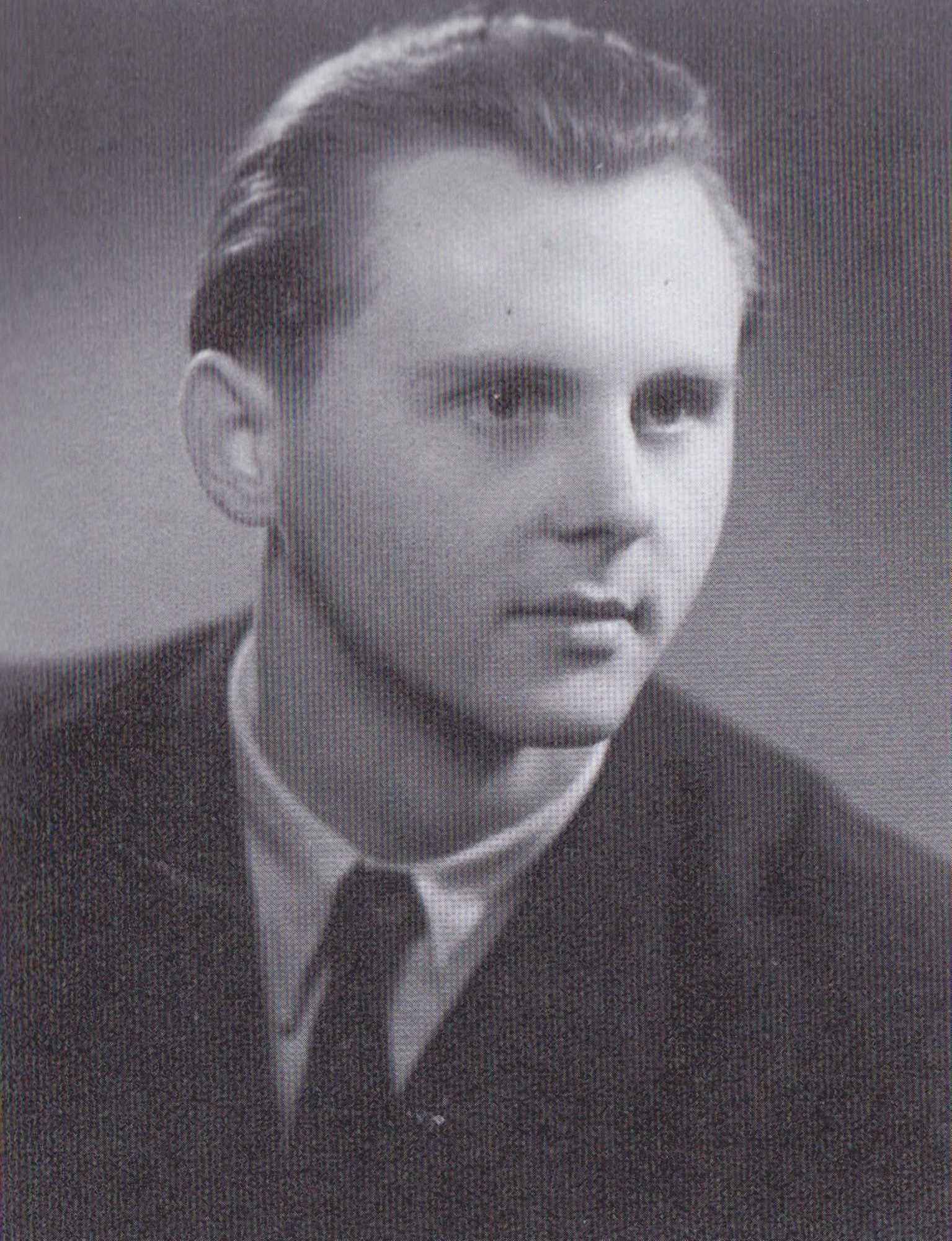

Jan Vývoda was born in 1924 in Hranice in Moravia. His father owned a tailor workshop but after 1948, he had to sack all his employees and work on his own. Jan Vývoda was a slave laborer during the war – he worked in Germany as well as in his native Hranice. After the war, he decided to assume the career of a clergyman and joined the Order of the Salesians. In 1949, he transferred to the Salesians‘ center in Kobylisy in Prague, from where he was taken away in the course of the operation K in 1950 and interned in the Osek monastery. After a few months, he was posted to the auxiliary technical battalions (PTP) where he spent over three years. After his return, he worked in a factory in Libčice nad Vltavou and then moved to Prague in 1965 and made a living by cleaning windows. In 1967, he was ordained as a priest by Cardinal Trochta and he had a stint in the Salesian parish. He retired in 1984 and is still active as a priest in Praha-Kobylisy.