To live so that you need not be amashed of your life

Stáhnout obrázek

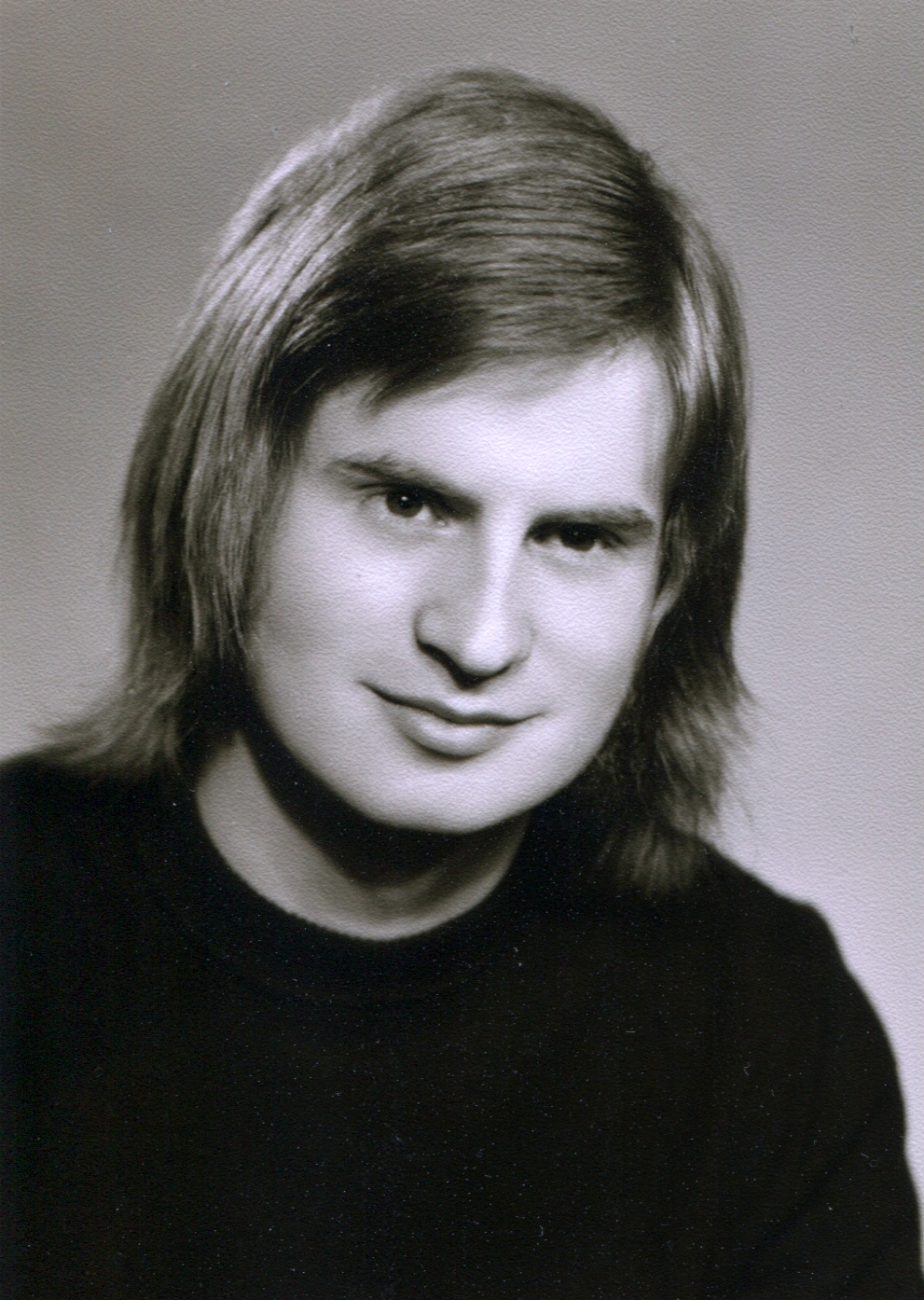

Daniel Ženatý was born in Moravský Krumlov on 12 December 1954, into the family of the Evangelical pastor Emil Ženatý. He grew up and graduated from secondary school in Vsetín. In 1974 he began studying at the Comenius Faculty of Protestant Theology in Prague. In 1980 he was drafted into compulsory military service in a motorised regiment near Benešov – unlike other students, who were only required to serve one year in the army under Communism, he had to serve the whole two years. From 1980 to 1990 he functioned first as a vicar and then as a parson in Valašské Meziříčí. It was there in 1982 that he met Milada Šimčíková (1900–1989), the last pupil of the famous singer Emmy Destinn, who had been incarcerated in the Ravensbrück concentration camp by the Nazis during World War II. In 1988 the witness made an extensive recording detailing Šimčíková’s life story. A considerable part of his own testimony focuses on her life. Ženatý experienced and actively took part in the Velvet Revolution while in Valašské Meziříčí. From 1990 he served as a parson in Nové Město na Moravě. At the turn of 1990 and 1991 he sheltered a young deserter from the Soviet army, Alexej Ženatý (born 1971). Since 2005 he has functioned as the parson of the Pardubice congregation of the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren. For seven years, from 2007 to 2015, he also served as a prison chaplain in Pardubice. Daniel Ženatý continues to be publicly active, has published several books, and has worked with Czech Radio. From 2015 to 2021 he was a synod elder of the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren, and in 2017 he was elected Chairman of the Ecumenical Council of Churches of the Czech Republic.