Freedom is everything

Stáhnout obrázek

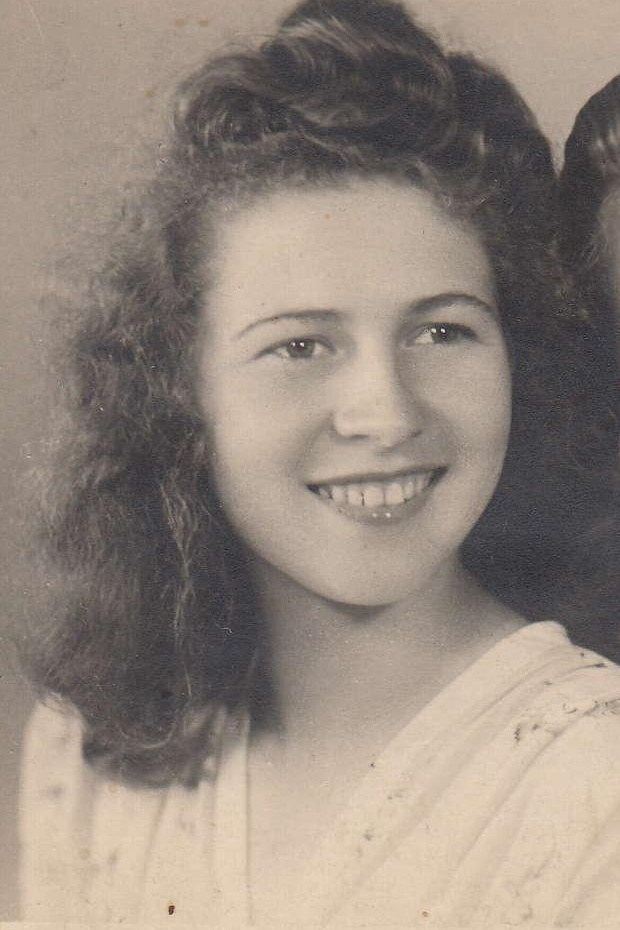

Anna Bařinová née Putnocká was born on August 3rd 1926 in Budkovce, Slovakia. Her mother, Marie, was of Hungarian origin, a fact due to which the family had been forcibly relocated to Slovak-Hungarian borderland in 1938. After her father, Štefan Putnocký, managed to convince the authorities him being a “pure-blood Slovak”, the family had been allowed to return to its previous place of residence. After the war, Anna decided to leave Slovakia as a nineteen-years-old. She started to work at Baťa Enterprise in Zlín. For a young woman, growing up in a remote settlement of Budkovice, it was an amazing experience. As the youth could enjoy music and dancing. For the first time, she experienced how it felt like to take a shower. In 1948, as a Revolutionary Trade Union Movement (ROH) member, she had attended the XI. All-Sokol Rally in Prague (Praha), where, in the strongly anti-Communist ambiance, the Sokols refused to let the Union members to the parade grounds. In the early 50s, she met her future husband, Zdeněk Bařina, in Zlín (Gottwaldov at that time). During the World War II, he had been supporting partisans with his father, who, indirectly, had been the cause for the Ploština massacre. In 1950, as signatures had been gathered for an open letter asking Klement Gottwald for a death sentence for Milada Horáková, Anna Bařinová refused to sign. After Bařina´s tailor workshop had been nationalized, the family left for Napajedla where they would spend most of their lives. In the 60s, Anna Bařinová´s husband, Zdeněk, joined the Communist party, leaving it after the Warsaw pact invasion of 1968. Speaking about the socio-political development following the Velvet revolution, Anna Bařinová states that most of all she values freedom, the most precious thing there is.