A thousand metres underground

Stáhnout obrázek

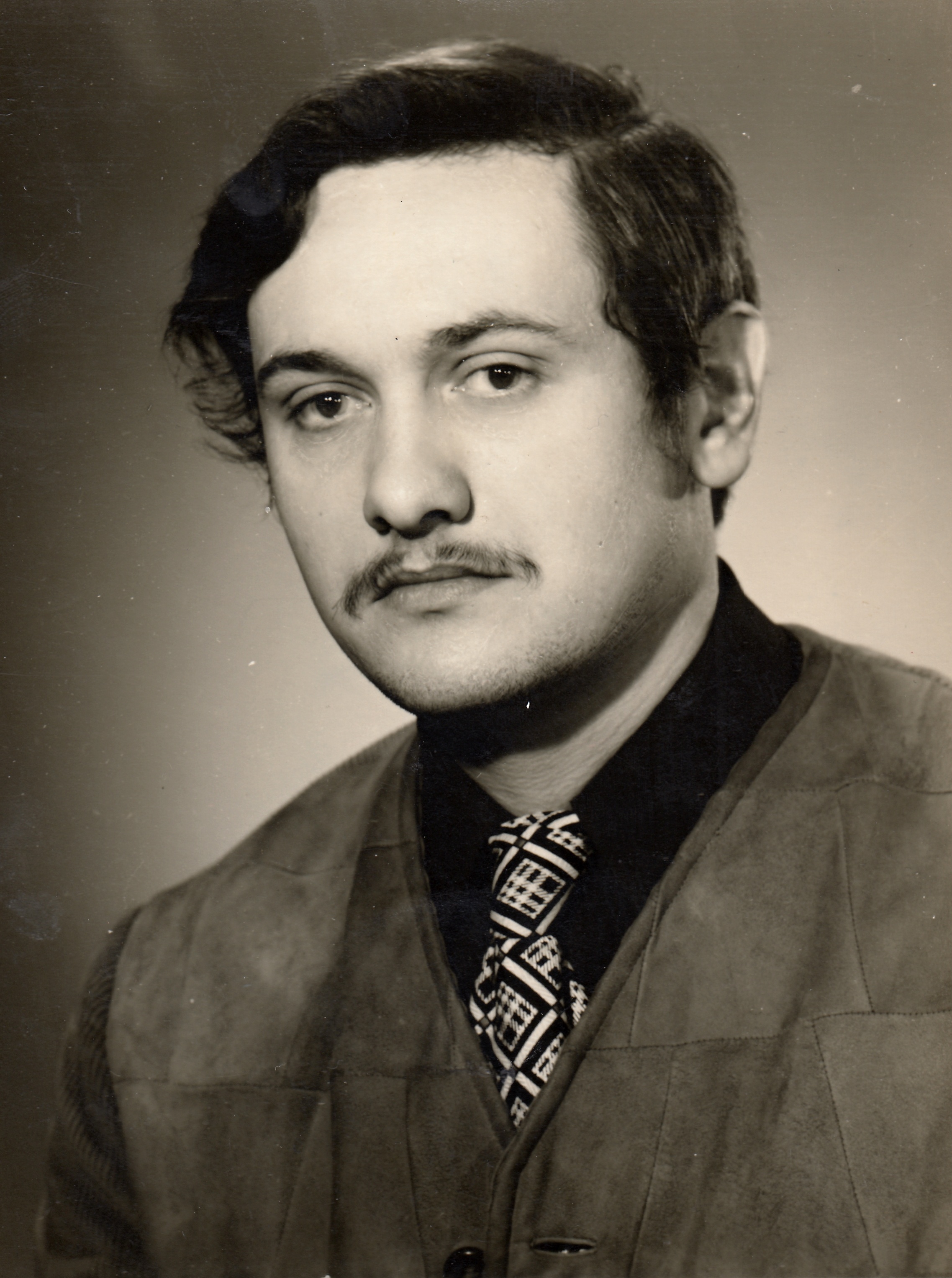

Jan Hradecký was born in the border village of Hraničná-Markhausen in the Sokolov region on 6 December 1947. The family did not stay there for long. After the communists came to power, the free movement of Czechoslovak citizens across the border was forbidden and passports without an exit clause were no longer valid. A border zone was declared. The new inhabitants of Hraničná had to leave again. In 1955, the village and the adjacent houses were levelled by government decision. Jan Hradecký and his parents moved to Kraslice. His father worked as a SNB officer. His mother Marie, née Mullerová, was a trained seamstress. Her dream of owning her own tailor shop was crushed in February 1948. She found employment in the nearby Oloví flat and mirror glass factory where she was in charge of labelling the plant equipment. Jan Hradecký trained as a miner. Having completed his military service with an engineering unit in Bohosudov, he worked as a miner until retirement. He spent most of his time at the Marie Majerová shaft, the last deep lignite mine in the Sokolov region. Jan‘s grandfather used to be a miner and witnessed the explosion at the Nelson mine in 1936 and the subsequent miner strikes in Most and Duchcov. Jan Hradecký is keenly interested in the history of his home of the past seventy-seven years. Kraslice is a town with a history typical of the borderland, from the rise of Czech Germans‘ nationalism in the 1930s to the usurpation of the Czech borderland by Hitler to liberation by the US Army in 1945 to the unfortunate post-war development with all the injustices of history both big and small that occurred over the ensuing decades. All the while, lignite was being mined a thousand metres deep under the ground. Jan Hradecký did so for thirty-three years. He retired after his final shift on 21 December 2002. He lived in Kraslice in 2024.