I couldn’t change myself. I was brought up like that

Stáhnout obrázek

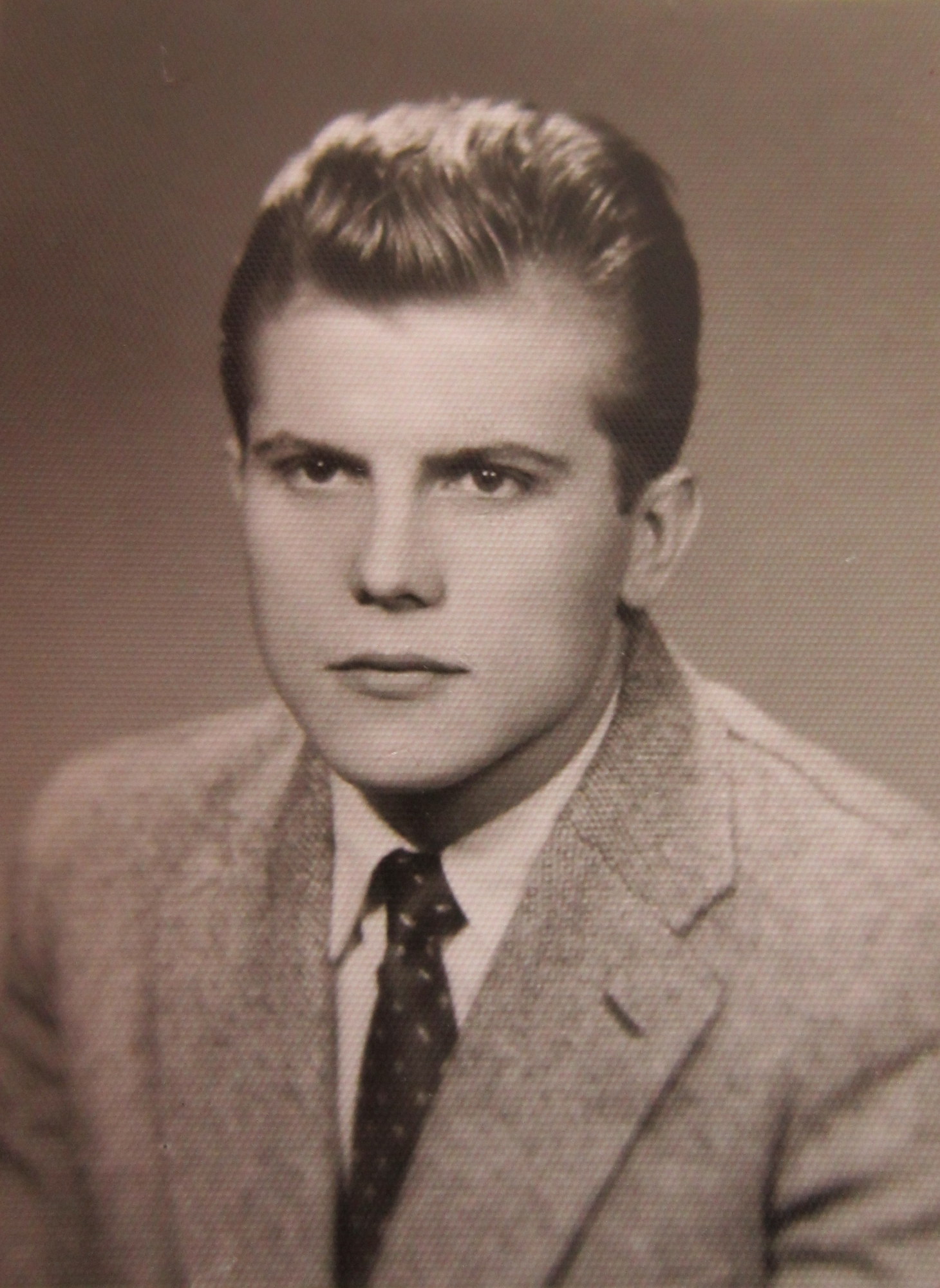

Pavel Kolínek was born on 26 November 1938 in Valtice near Břeclav. Since his childhood he has been a member of the Seventh Day Adventists, which caused him much trouble during the Communist totality. Already as a primary school pupil he found himself standing before a court because as an Adventist he did not attend Saturday lessons, which were mandatory at the time. Later, during compulsory military service, his faith caused him to be targeted by his commanding officers, and a court sent him to prison for two years for allegedly avoiding his duties. After the death of President Antonín Zápotocký, an amnesty was declared and Pavel Kolínek was released after only a month and sent back to the barracks. But two weeks later he refused to obey an order on a Saturday, and he found himself before a military court once again; this time he was sentenced to two and a half years of prison. Even in prison he observed the Saturday, which brought him repeated stays in solitary confinement. In total, he spent more than seventy days in the concrete tomb underground. They released him two months before the end of his sentence as part of a big amnesty in 1960. He then started work as a miner in the Petr Bezruč Mine in Slezská Ostrava, and he remained a miner until his retirement. He now lives in Ostrava.