I don‘t regret anything, it´s not worth it

Stáhnout obrázek

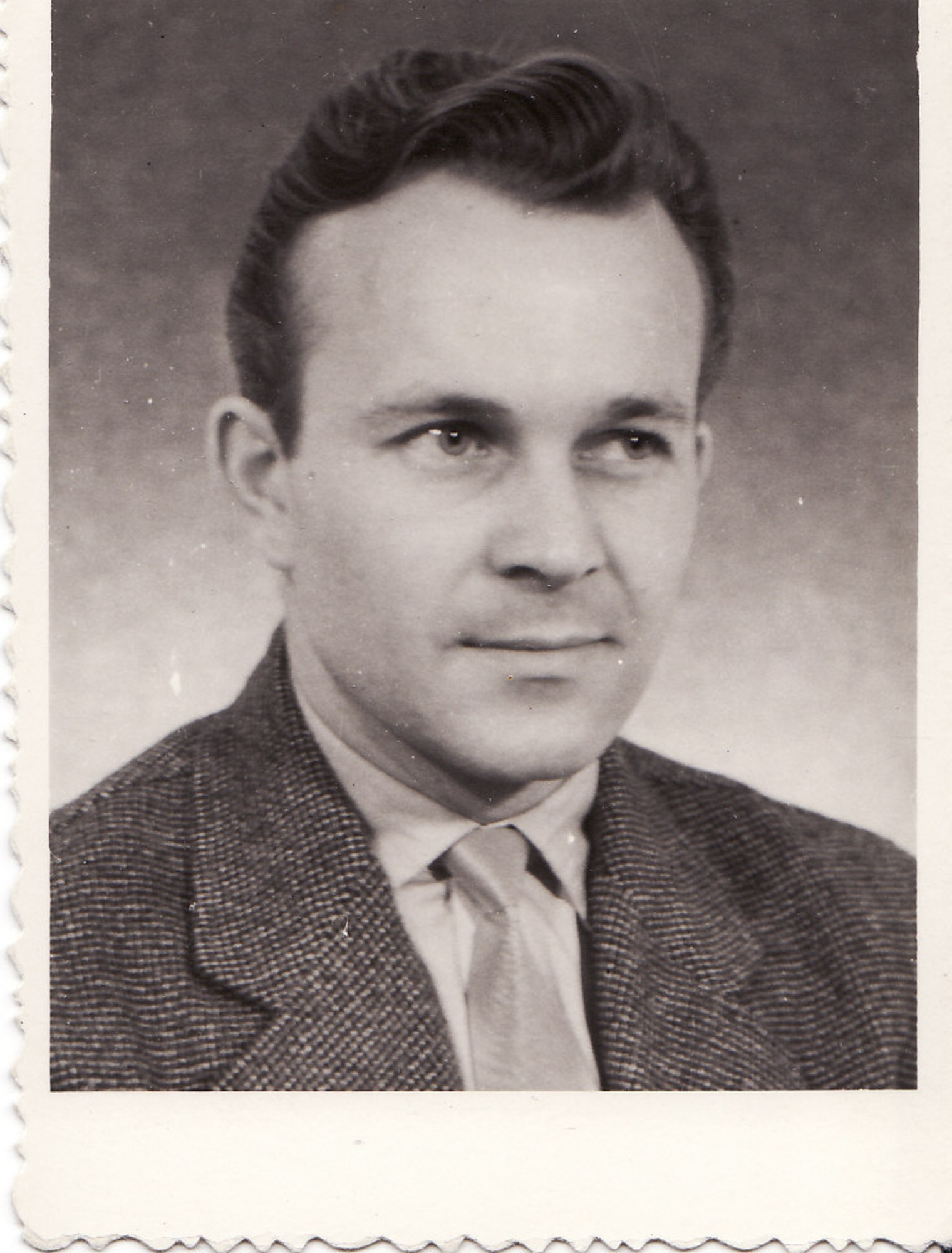

Vlastimir Maier was born December 30, 1932, in Postřelmov (Šumperk district). After the communist putsch, he and his friend founded a resistance group called Expres. They attacked local communist officials and printed anticommunist pamphlets. In April 1951, he was arrested and in the same year, he was accused of espionage and high treason. The death penalty was impending in his case. He was sent to labour camps in the Jáchymov region. He passed through camp XII (camp of death), Prokop, Barbora, Vykmanov, Vykmanov II (camp L) and Nikolaj; he also worked in the feared Tower of Death, where the sorting of highly radioactive uranium was carried out. After that, he refused to continue working in the mines. He spent three weeks in a „correction cell“ and then was sent to the Leopoldov prison. He was released in 1960. Altogether he has spent ten years in camps and prisons. After his release, he returned to Postřelmov, until his retirement he worked at the local company MEZ. He is the chairman of the Confederation of Political Prisoners in Šumperk. At present, he lives in Postřelmov.