I was always proud of the Communist Party. I never grew bitter towards it

Stáhnout obrázek

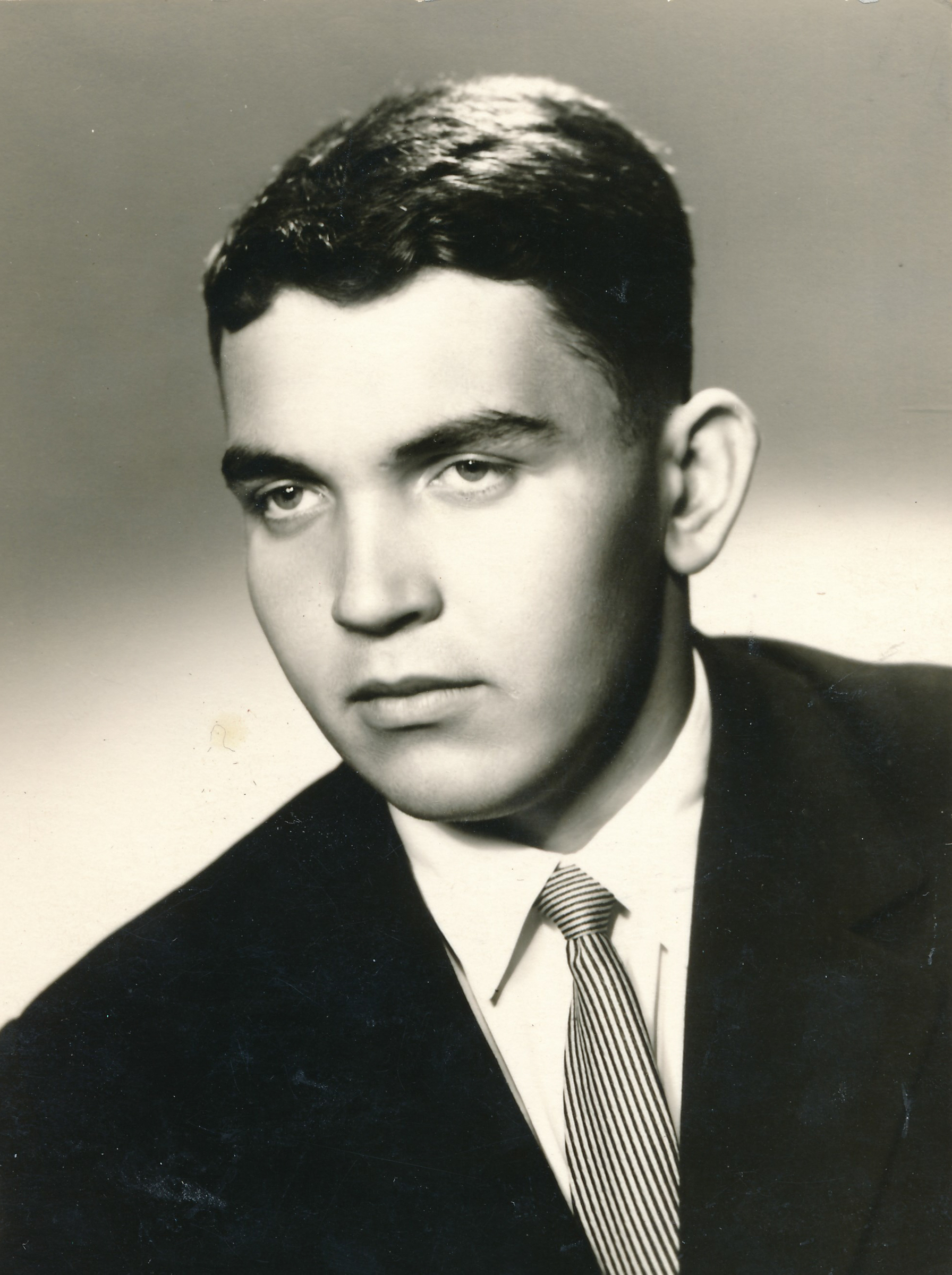

František Merta was born on June 13, 1944, in Prague. His two uncles were members of the Defence of the Nation resistance movement during WWII and were arrested for their activities. Uncle Jaroslav Evald was executed in March 1943 in the Berlin prison of Plötzensee. The father of František Merta was a member of the Sokol resistance, in 1945 joined a resistance group organised by the communists and after the war joined the Party. František Merta went to study grammar school in Šumperk and later went on to study medicine but abandoned his study against the will of his parents. For another half a year he worked as a driver’s assistant at ČSAD (Czech transport company), then started studying at Mendel University in Brno. In 1962 he applied for Party membership and two years later became a member of the Communist Party. On graduation he went to serve in the military and witnessed the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact armies as a second lieutenant in Aš and Cheb. After his military service he passed normalisation checks and himself took part in such a committee in Velamos in Roudnice nad Labem. In 1971 he joined the Party administration in Šumperk. Three years later he was delegated to study the Political University run by the Communist Party. In 1980 he became the district secretary of the Party in Šumperk and held the post until the Velvet Revolution. In 1996 he was an unsuccessful candidate of the Communist Party for the Senate. Currently he is a member of the municipal board of Šumperk.