Something‘s rushing in, there‘s going to be a war, we all need to be together

Stáhnout obrázek

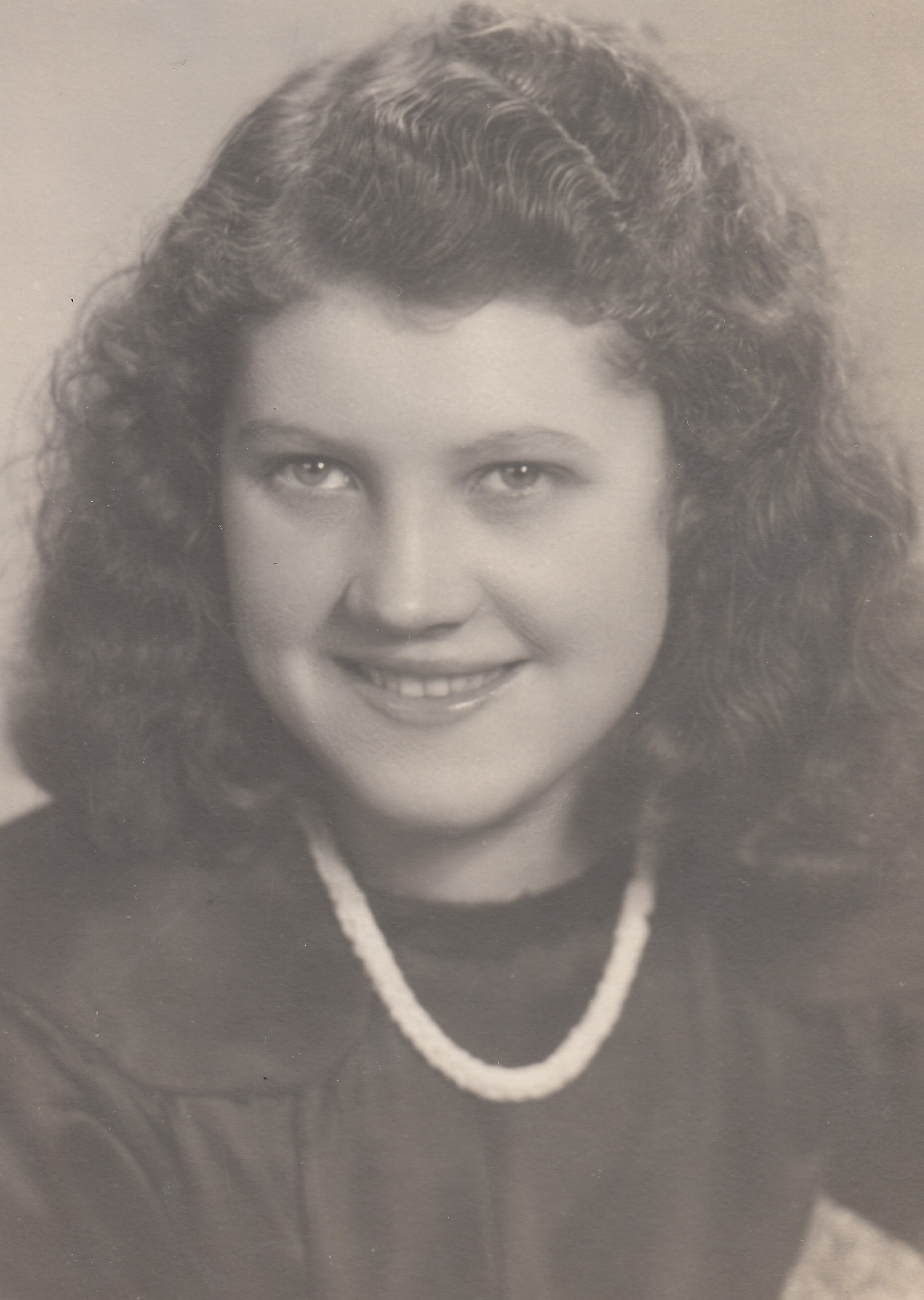

Helma Růžičková, née Koubová, was born on 10 August 1933 in Petřkovice near Ostrava. Her father Hubert Kouba (1906-1981) was Czech, her mother Elizabeth, née Weidlich, (1909-1989) was German. Helma had a brother Hubert, born in 1932, and František, born in 1940. In 1939, the Koubas moved to Breslau, Germany (today‘s Wroclaw) to stay with their aunts, and shortly afterwards to Brieg (today‘s Brzeg, Poland). Her father worked in a factory there, her mother took care of the children. However, the situation there was becoming more and more dangerous, with more air raids. Her mother always urged the children to run back home so that they would all die together. On 19 March 1945, her father took them to Vidnava, hoping that they would live there through the end of the war with their grandfather and grandmother. He himself worked in Donauwörth, where the factory had moved. However, when the front approached, Elizabeth and her three children had to leave Vidnava. With only the essential belongings, she fled with other refugees in open railway carriages. They reached Králíky, where they were taken in by the German couple Doležal. After the factory in Donauwörth had been bombed, her father Hubert followed the family to Králíky on foot. In May 1945, Soviet soldiers appeared in Králíky. All the Germans were afraid of revenge, and the women were also afraid of rape. The Koubas would often hide German women for this very reason. The entire family on her mother‘s side, with whom Helma spent her childhood, was expelled after the war. As a mixed marriage, the Koubas were allowed to stay. Helma felt sad that she would never see her grandfather, grandmother, cousins, aunts again. She would have preferred to go with them. Like her mother Elizabeth, she had a long and difficult time coming to terms with the separation of her family. After completing primary school in 1948, Helma went to work as a labourer in a textile factory. Being a bright and intelligent pupil, she wished to teach in a kindergarten, but because of her background and relatives in the West, the communist regime did not allow her to study. In 1954 she married Jiří Růžička (1928-2008), but even marriage did not improve her cadre profile, because her husband‘s father was a political prisoner of the 1950s. The newlyweds settled in Dolní Morava, where Helma was a shop assistant in a grocery. Three children were born to them in 1955, 1956 and 1963. In 1964 they moved to Nekoř. There Helma also sold in a shop, in total, she was a shop asssistant for thirty years. In the same year she was allowed to travel to Germany for the first time to visit her grandmother and aunts. The experience of existential fear for her children, which she had felt from her mother during the war, was felt by Helma on 21 August 1968, when the Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia. Like her mother, she felt a strong need to keep her loved ones close to her so that they would all be together in case of death. In her life, she did not divide people by nationality and she did not reprobate anyone. She was living in Nekoř in 2021 and as a message to the younger generation, she told them to be honest and hardworking.