We always counted on eavesdropping, wrote on post-it notes at home.

Stáhnout obrázek

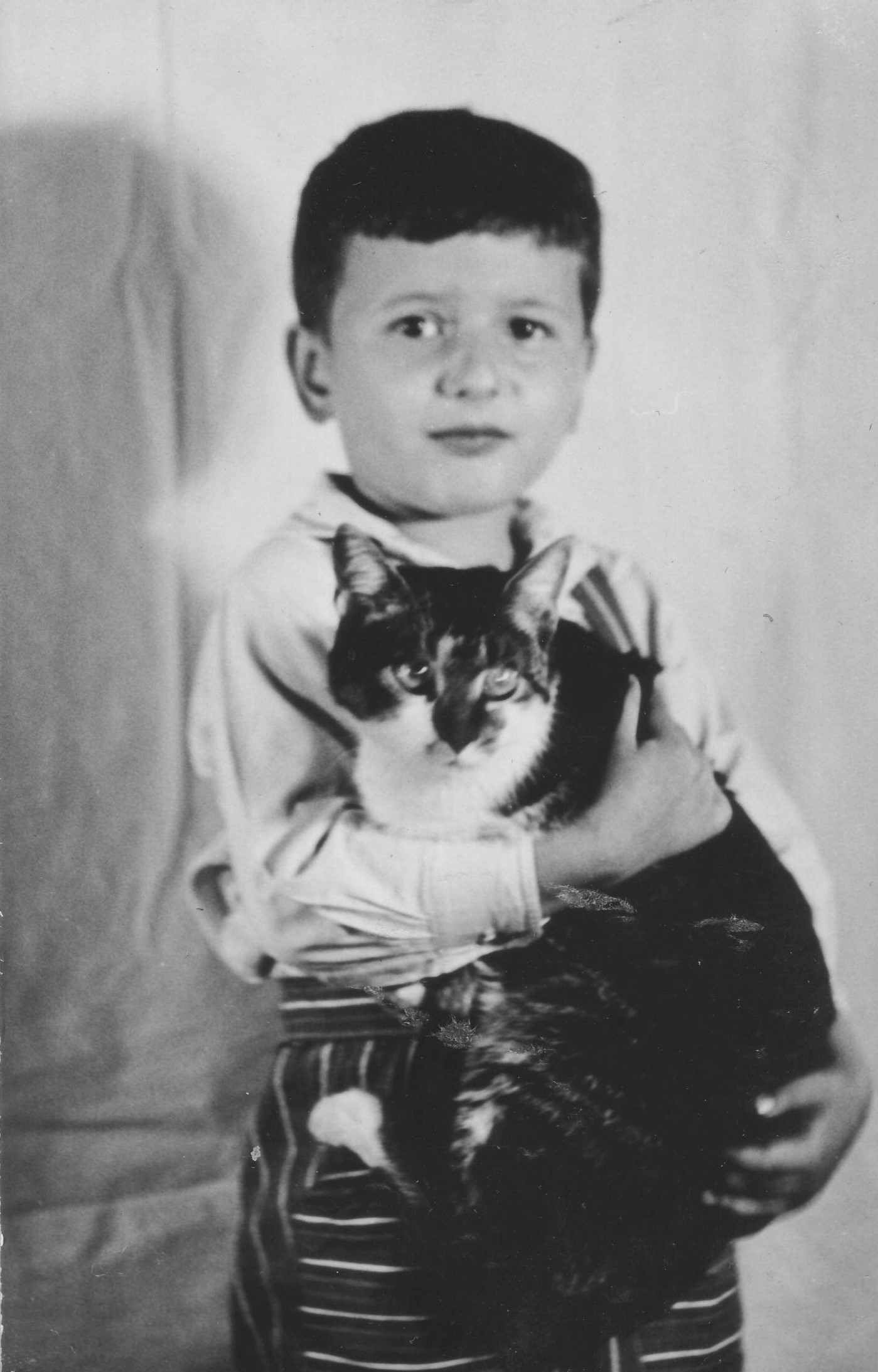

Jan Vaculík was born on 23 May 1958 to parents Ludvík Vaculík and Maria Vaculíková, called Madla. He was their third son and grew up with his older brothers Martin and Ondřej. His childhood was influenced by his parents‘ activities. The family was bugged by State Security Service (StB), and both parents had to appear frequently for interrogations. He spent his childhood partly in Prague and partly in Brumov, his father‘s hometown. After the occupation by Warsaw Pact troops, his eldest brother Martin emigrated to France. Jan Vaculík was not admitted to high school three times because of his unfitness for the cadre. First he worked as a surveyor, then he trained as a car mechanic. Later, he graduated from a secondary school for workers and finally got into the Czech Technical University. He worked in the Orpheus Theatre under the direction of Radim Vasinka. In the late 1980s, he was prosecuted for participating in a demonstration. He worked at the Czech Shipyards, and after the revolution he started his own business in a company producing measuring instruments. He is married and has two children. In 2024 he lived in Dobrichovice.