I wanted to save face and say what I didn‘t like

Stáhnout obrázek

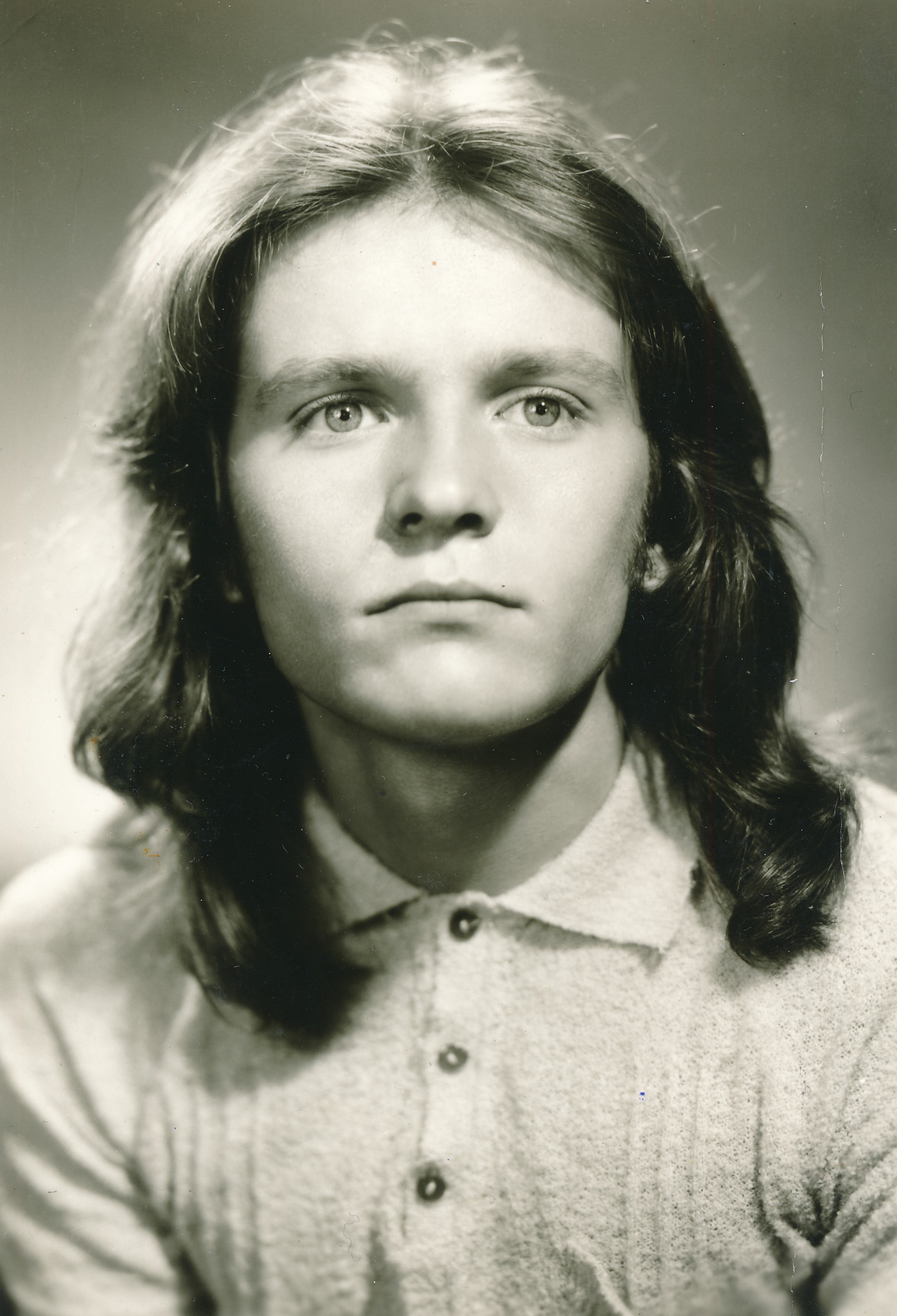

Josef Vozáb was born on 16 April 1955 in Karlovy Vary to Rozálie and Josef Vozáb. In 1970-1974 he studied at secondary technical school with a focus on the production of musical instruments in Kraslice. In 1974-1976 he served in the army in Liptovský Mikuláš. Then he worked for a year in the Karlovy Vary Youth Home, where he spread the Charter 77 among the students. As an individual, he tried to fight against the regime, he was not in close contact with dissidents. In 1981, he signed Charter 77, but his signature was not made public. The following year he did so again, at the Palouš family in Prague. Since then he has been under surveillance by State Security (StB). They regularly interrogated him and offered him cooperation, which he refused. In 1983, as part of the Asanace action, they began to pressure him to move to Austria. A year later, he received permission and left for Vienna with his wife. In 1989 they were granted citizenship. Between 1990 and 1992, the witness studied nursing and between 2001 and 2004 psychiatry. He worked in the health care sector until 2015. He returned to the Czech Republic in 2019. In 2024, he was living near Prague.