Now it comes to the point, there is a unique thing that I consider very important, there comes a moment when you yourself have to hold a parliamentary session. Because the following happens: Gorbachev... Now I... I have those things written down, but now I may not remember when [was it]… It was autumn, so Gorbachev saw that the country was collapsing, the republics started to leave, some centrifugal forces were working, and he decided that it was necessary to sign a new union agreement/treaty, to give the republics new rights, and to say: “well, we give you this much, let’s sign it again, let’s unite and create a new union.” Why were we worried about that, why? Because we were thinking that now they would adopt this in the center, in Moscow, they would say yes, you would have to live like this. So, how could we prevent it? To prevent it the Parliament of Armenia, in this case the Supreme Council, needed to adopt a special decree, a law, that any decision, any law, which would be adopted at the level of the Union, would be effective on the territory of Armenia, only if it would be approved, ratified by our parliament.

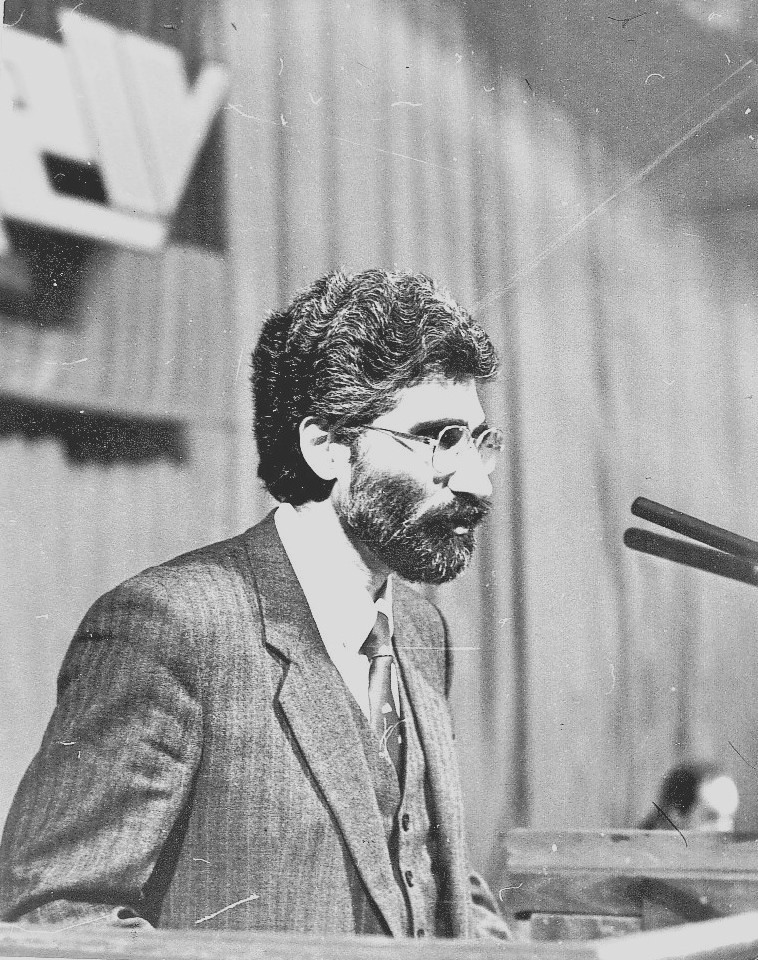

Well, now we say let’s do something, let’s do that session. Unsurprisingly, the leadership refused to do it. Ok, you don’t do it, in that case, how is it written in the law, let’s say, the session can be held if a certain percent of people, say one-third demands it, no? Well, maybe. If it is possible, then we collect the signatures. We collected the signatures, the session should be scheduled. They do not give us a space, i.e. the hall of the Supreme Council. They don’t provide us with the space, we do it at the Opera. And here it was a unique thing, when an official Supreme Council meeting was organized in the Opera Hall, in November. Moreover, look, there should be a quorum. Now, those people are mostly ordinary people. One is a factory director, one is an advanced worker, another one is a party worker, I don't know what, there is a big number of people. But they have to come, and it is to gather them… Most are coming. First of all, they came, because at the end of the day they all were ultimately patriots, regardless of what their party affiliation was, and partly because it felt uncomfortable, since if you did not come, people in groups, in large groups, from the regions, they surrounded your house with the words “Shame! Shame! Shame!” And you are a human being, you are sitting at your house, you have children, grandchildren. They came, because it felt uncomfortable. And Ashot Manucharyan kept coming out and saying: there are this many people, there are that many people, this many are needed for the quorum. We organized the quorum. We adopted the decree, but on that day, on that same day, unrest already started in the Sevan basin between Azerbaijanis and Armenians, organized in some way, after which a state of emergency was declared immediately on the same day, everything was frozen and everything was closed.