We have lived on our farm since 1469

Stáhnout obrázek

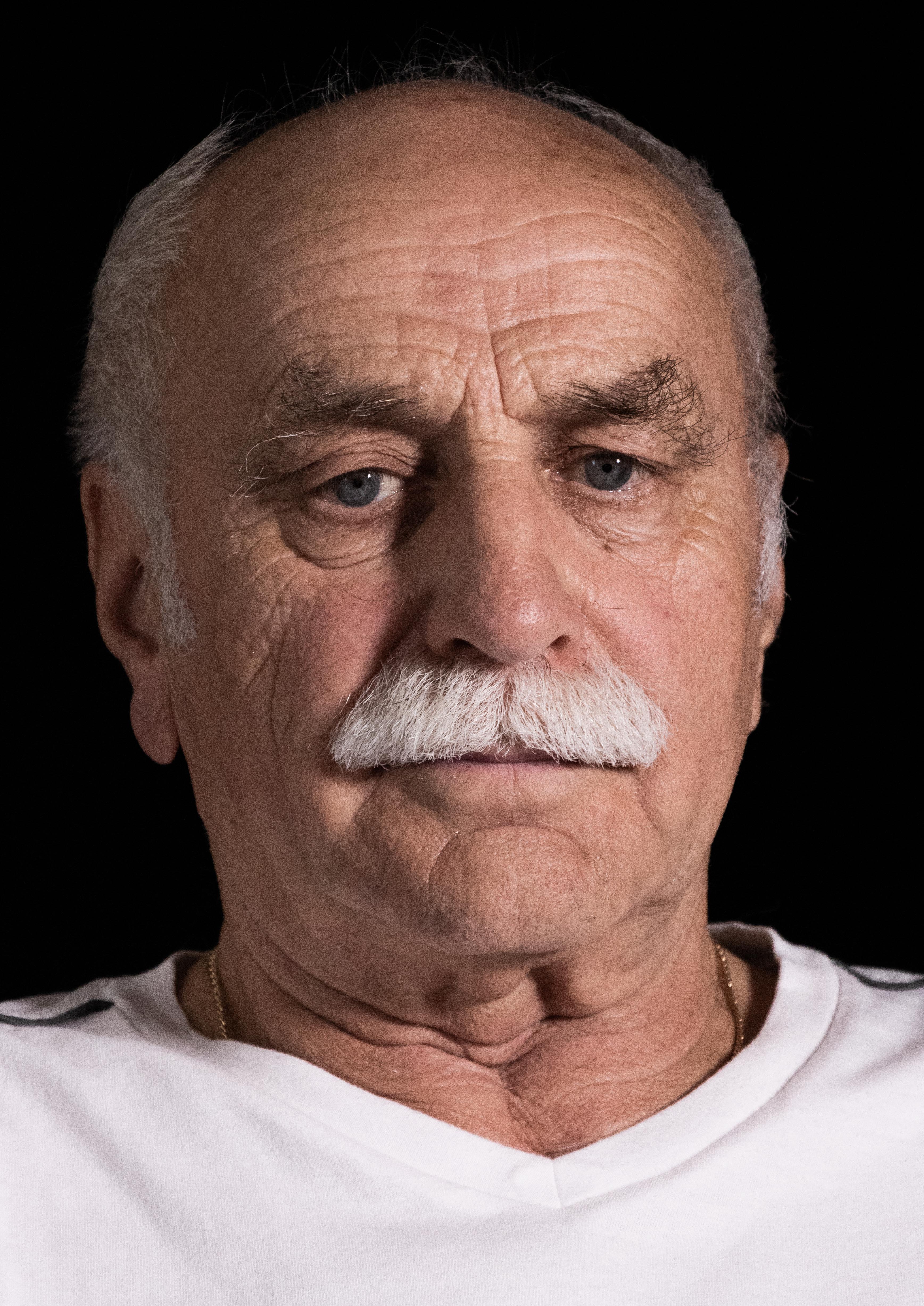

Adalbert Schiller was born on April 11, 1942 in the village of Lšelín near Stříbro. His family had the family farm since the 15th century. In September 1946, the Schillers were deported to Bavaria. They found a new home in the district of Nayla, first in the town of Bad Steben, later in the district town itself. It was not easy to make a living for a large family (13 children). Adalbert Schiller trained as a car mechanic and spent almost his entire professional life selling cars. In addition, however, he was also very socially active - he worked in the leadership of the Catholic Workers‘ Movement and also in a football club, where he played football for many years and successfully. In 1972 he joined the Sudeten German Landsmannschaft, where he held various positions. He has a very strong relationship with his old homeland and often travels to the Czech Republic. He and his wife raised four children.