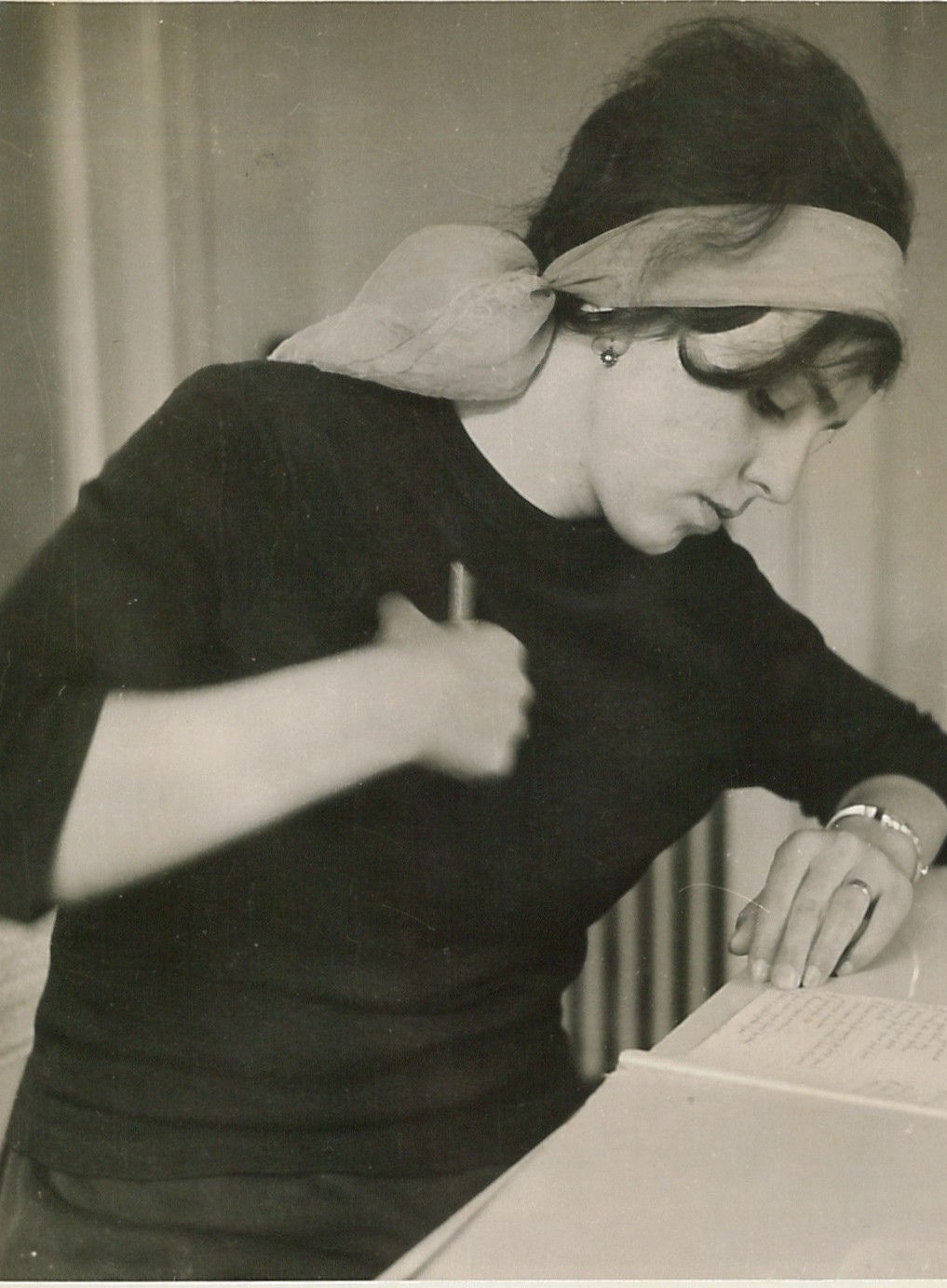

She wanted children, so she knit a pouch to protect her husband’s testicles on the frontline

Stáhnout obrázek

Růžena Teschinská, née Lamačová, was born in Smržovka on 2 May 1946. Her mother came from a Czech family in the Kolín region and her father from a Czech family in Smržovka. One of his ancestors likely had genes of the Walderode noble family, as he was an extramarital child of a nobleman and his maidservant. Růžena Teschinská married a man of German origins in 1964. Her daughter Inka was born the same year and son Oto was born in 1973. Růžena Teschinská’s father-in-law fought on the eastern front near Moscow in World War II; he was injured and recovered by the Baltic Sea. Having returned to war, he was captured in France and stayed there as a labourer for several years. He came back home around 1950; a son aged seven awaited him. Růžena Teschinská condemned the Warsaw Pact occupation of 1968. Her daughter paid the price – she was not admitted to university due to her mother’s poor ‘cadre profile’. Růžena Teschinská completed an applied art high school and worked as a metal bijoux painter, then in a showroom, in a toy factory, in a shop, and in a family restaurant. Following the Velvet Revolution, she witnessed the bankruptcy of the bijou factory she had worked with. She was living in Smržovka in 2022.