My patriotism happened in Czech literature

Stáhnout obrázek

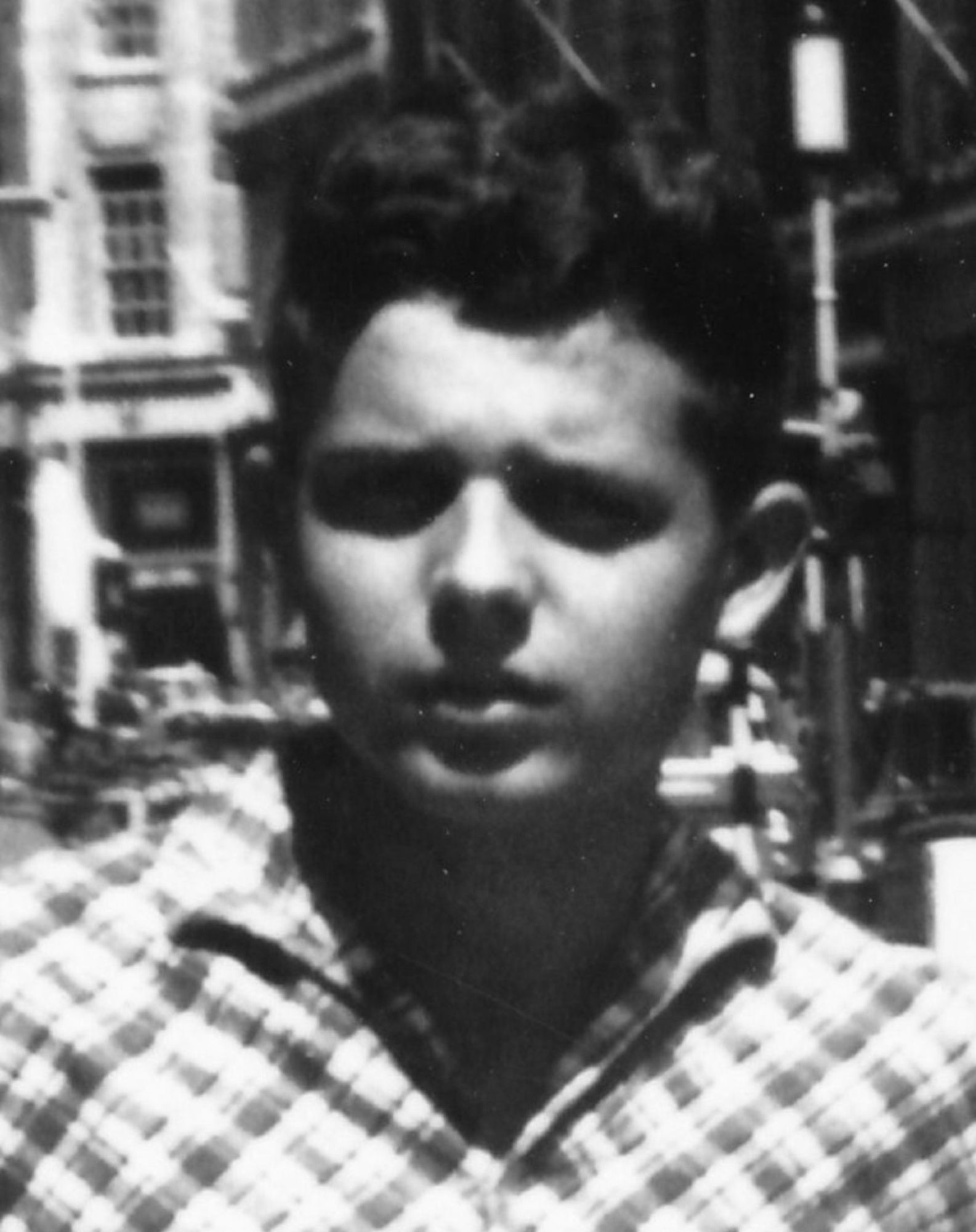

Alexander Tomský was born on December 13, 1947, in Frýdlant into a family of an archaeologist and histologist. He studied at the grammar school in Pardubice and was accepted for the study of aesthetics at the Faculty of Arts, Charles University Prague. On August 21, 1968, he emigrated via Austria to the UK, where he studied international relations at London School of Economics. He worked as administrative and organisational staff in construction, an officer in an insurance company and a teacher. Later he was employed as an analyst of Keston College, an organisation monitoring the persecution of Christians in the East Bloc countries. He established the exile publishing house Rozmluvy, served as the director of the charity organisation Aid to the Church in Need. After 1989, he served as the director of the Academia publishing house, run by the Czech Academy of Sciences, while lecturing at the New York University in Prague. Today he works as a journalist commenting on public life.